http://preferredmode.com/?p=739 I have always had concerns about outsourcing tax debts to private collection agencies (PCAs). First, I believe tax collection is an “inherently governmental function” within the meaning of section five of the 1998 FEAR Act that should be performed only by federal employees. Second, as a TAS study of the last private debt collection (PDC) initiative showed, the IRS is more efficient at collecting tax debt than PCAs are. Now that Internal Revenue Code (IRC) § 6306(c) requires the IRS to outsource some tax debt, my job is to ensure that its PDC program operates in accordance with the law and respects taxpayers’ rights. As I described in my 2016 Annual Report to Congress and in my recently released Fiscal Year 2018 Objectives Report to Congress, I believe the new PDC initiative inappropriately burdens taxpayers who are likely experiencing economic hardship, including those with incomes at or below the federal poverty level.

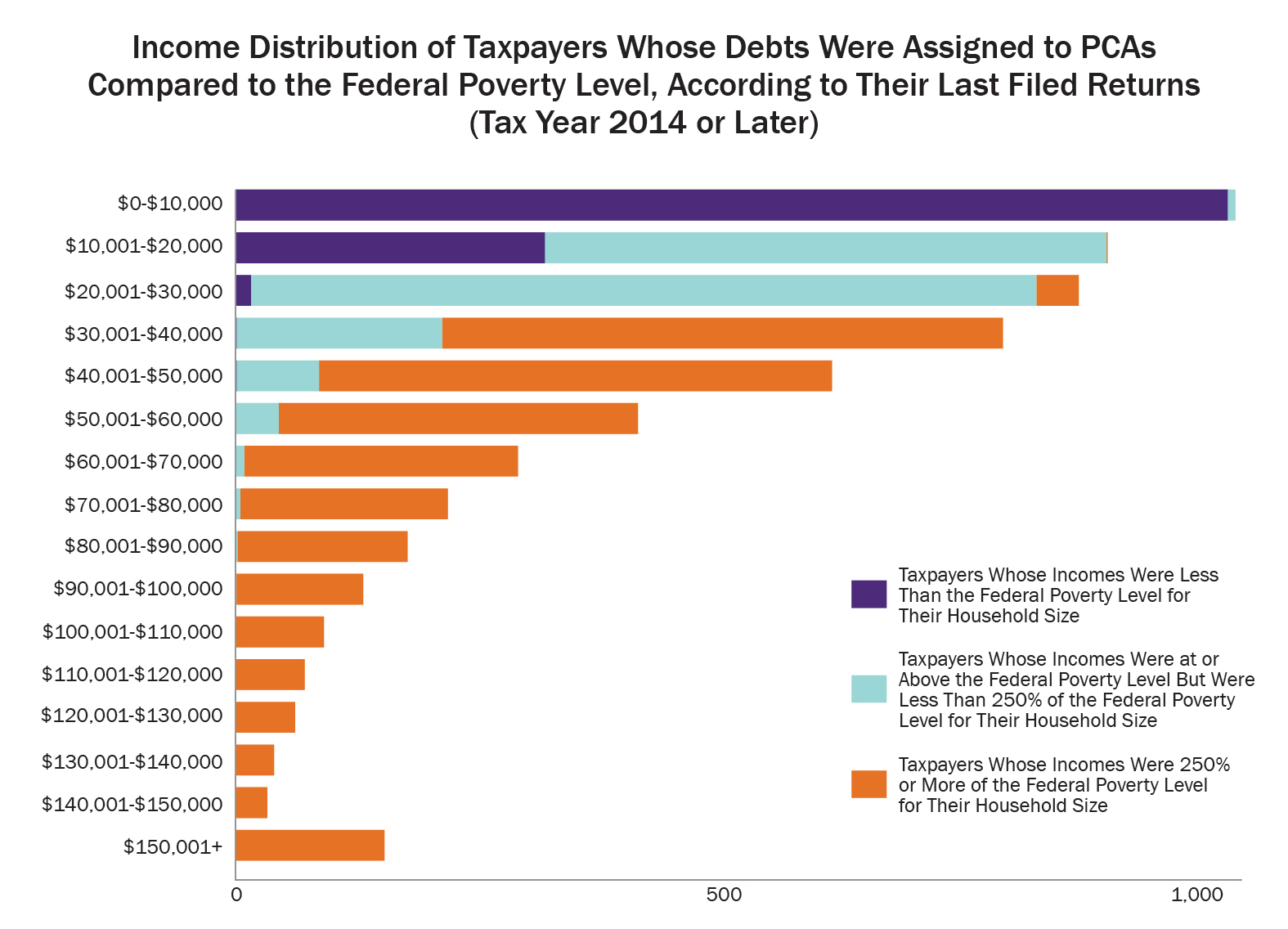

isotretinoin no prescription As of May 17, 2017, the IRS had assigned to PCAs the debts of approximately 9,600 taxpayers, approximately 5,900 of whom filed a recent return. The returns show:

- These taxpayers’ median annual income is $31,689;

- More than half have incomes below 250 percent of the federal poverty level; and

- More than a fifth have incomes below the federal poverty level.

Here is the income distribution of taxpayers whose liabilities were assigned to PCAs as of May 17, 2017, compared to the federal poverty level.

As the Figure shows, more taxpayers belong to the income category of less than $10,000 than to any other category. These 1,041 taxpayers comprise 18 percent of the total, and the incomes of all but eight of them are below the federal poverty level. Almost half of the taxpayers – 2,827 or 48 percent – have incomes of $30,000 or less. Of these taxpayers, only 45 percent have incomes equal to or more than 250 percent of the federal poverty level.

Taxpayers at these low income levels are more likely to be vulnerable – more likely to speak another language, have a disability, be elderly, and have a lower level of education – as compared to taxpayers with higher incomes. They are also more likely to be perplexed or scared and more likely to make unnecessary payments. For this year’s Annual Report to Congress, we’ll be analyzing the accounts of taxpayers who have made payments to PCAs or entered into installment agreements. We’ll see how those arrangements stack up in terms of the federal poverty level and whether they leave taxpayers with less income than their allowable living expenses.

Even if the PCA is unsuccessful in collecting from the taxpayer and sends the case back to the IRS, the case will likely sit on the shelf in inactive status. The taxpayer will have to contact the IRS directly and provide financials to get into Currently Not Collectable (CNC) Hardship status. An IRS assistor, on the other hand, is more likely to unearth the fact that the taxpayer would likely meet CNC Hardship status and would then inform the taxpayer of what steps to take to avert enforcement action.

To its credit, at my urging, the IRS agreed to not assign to PCAs the liabilities of taxpayers who receive Social Security Disability Income (SSDI). These taxpayers by definition generally cannot earn more than $1,170 per month ($1,950 if he or she is blind) without having their SSDI payments reduced. Because of the IRS’s earlier refusal to exclude these debts, however, the necessary programming was not in place by the time the IRS began assigning tax liabilities to PCAs. Thus, as of May 17, 2017:

The debts of 445 taxpayers who received SSDI in 2016 were assigned to PCAs;

Of these 445 taxpayers, 160 filed recent returns; the median income shown on these returns was less than $10,600.

I also urged the IRS to consider not assigning to PCAs the liabilities of taxpayers who were not subject to levies on their Social Security Administration (SSA) retirement payments pursuant to the Federal Payment Levy Program because their incomes were at or below 250 percent of the federal poverty level (see IRM 5.19.9.3.2.3, Low Income Filter (LIF) Exclusion). The 250 percent measure operates as a proxy for economic hardship. In response, the IRS decided that for the first six months of the PDC program, these taxpayers’ debts would be included in the PCA inventory. The idea was that during that time, the IRS could explore how to identify taxpayers in this group who also have substantial assets. However, the IRS recently informed us that it intends to continue assigning these taxpayers’ debts to PCAs. As of May 17, 2017:

The IRS assigned to PCAs the liabilities of 875 taxpayers who received SSA in 2016;

Of these 875 taxpayers, 326 filed recent returns; the median income shown on these returns was less than $13,200.

The liabilities of taxpayers at these low income levels are so likely to be uncollectible that it is shameful the IRS doesn’t use this data to place these taxpayers’ accounts in CNC Hardship status instead of sending them to PCAs that cannot place the accounts into CNC Hardship status or assist with any other collection alternative. They will simply solicit payments the taxpayer may not be able to afford.

In light of the impact the current PDC initiative is having on taxpayers, particularly those experiencing economic hardship, I have determined that a compelling public policy warrants assistance to taxpayers whose debts have been assigned to PCAs. That means that these taxpayers qualify for assistance from TAS even if they don’t meet our usual criteria for case acceptance. In a later blog, I’ll explain why I believe the IRS in implementing the PDC program might also not be making good business decisions.

Read more about the Private Debt Collection (Part 1of 3).

Read more about the Private Debt Collection: Recent Debts (Part 3 of 3).